Eye in the Sky Giving a Leg Up in Vole Control

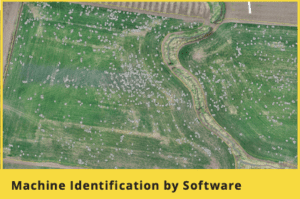

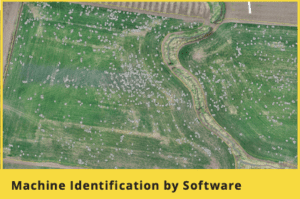

In the system, a drone is used to identify where voles are in fields by pinpointing vole holes. Stroda says the system is particularly valuable in young stands, where vole activity is more isolated and harder to detect than in older stands. “I think there is a benefit in the drone in monitoring these younger stands and not letting the size of those colonies grow,” he said. “You are targeting small areas, and you can go after it aggressively, and the drone lets us see where those areas are.”

Stroda also likes that in winter months, when above-ground baiting is prohibited, he can send crews right to hotspots, rather than have them walk an entire field.“By not having to walk the whole field, you can just go to targeted areas, get over a lot more ground and save a lot of labor,” Stroda said. “And in the summer, we are able to apply bait just in those zones, instead of having to bait the whole field.”

Stroda, who has used the Vole Application Mapping system three times now, said that in one field, the money he saved in bait costs alone paid for use of the system.

Ideal Habitat

Endemic to the Willamette Valley, the gray-tailed vole thrives in grass seed fields, where perennial stands provide it ideal habitat. Its long breeding season – voles breed from May through December – and a short reproductive cycle of about forty days are ideal for population explosions, and growers have suffered significant crop losses to the pest over the years. Voles kill grass seed plants by feeding on stems near the soil surface, essentially logging plants.

Vole populations typically have crashed the year after exploding, but that wasn’t the case with the most recent cycle. High vole population levels carried over from 2020 into 2021, costing the Oregon grass seed industry hundreds of millions of dollars in treatment costs and crop losses each of the past two years, according to Steve Salisbury, research and regulatory coordinator for the Oregon Seed Council.

Stroda, for example, said he spent $60,000 on rodenticide bait alone last year, in addition to his labor costs. Oregon State University Extension agent Christy Tanner, who also is working on drone technology to measure vole pressure – in her case to facilitate research projects – hasn’t seen the Vole Application Mapping system at work, but said that if it performs as advertised, it could be a valuable new tool in vole control.

“I think if we can get a good idea of where the voles are in a field and target those areas, that is going to save on bait costs and that is going to save on labor costs,” Tanner said.

Several Iterations

The Vole Mapping system, which was developed by two Wilbur-Ellis researchers with help from James Hilary of the commercial drone service company AeroTract, has undergone several iterations, according to the developers. But, from the start, the developers saw its promise.

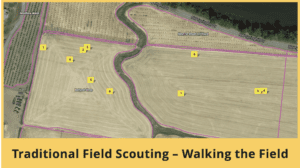

In its first iteration, conducted in the fall of 2020, for example, drone images showed much more vole pressure than a ground crew had observed by walking the same field just days earlier.

“We walked the field four feet apart and went up and down the field marking where we found holes,” said Devesh Singh, a technical agronomist for Wilbur-Ellis. “Then we looked at the image James (Hilary) had up on the computer, and when we compared the two, we realized we missed a lot of holes. And we realized that if a grower is walking a field like that, they too are probably missing a lot of holes. So, we said to James, ‘Okay, let’s move this thing forward.’”

Hilary hired a software programmer to refine the system, which involved teaching a computer how to identify vole holes, including differentiating a vole hole from a crack in the soil, and, after multiple iterations, many flights and hundreds of hours of artificial intelligence programming, the system was up and running.

Ground Truthing

Singh and Tanner Hendricks, a technical services specialist for Wilbur-Ellis, have spent many hours ground-truthing the system, and to date, all findings show the system is doing what it is purports to do. “It has been incredibly accurate in all of our ground-truthing work,” Hendricks said. “The resolution is in centimeters, so it is incredibly high-resolution imagery that we are dealing with here.”

He added that it takes about thirty minutes for the drone to fly a ninety-acre field. Wilbur-Ellis, in collaboration with AeroTract, now hopes to scale up the operation to cover more ground and service more growers. Eventually, Singh said, the team hopes to use drones to variable-rate apply bait.

“What we hope to do is upload those vole maps into the drone, and the drone can go and apply the bait,” Singh said. “That is the concept we are working on.”

Variable-rate application by drone is expected to be particularly valuable during late spring and early summer, when grass plants are tall and growers are hesitant to drive application equipment over fields.

In the meantime, the Vole Application Mapping system is helping growers zero in on vole pressure and reducing vole-control costs.

Download the Willamette Valley Sell Sheet on this Drone-Based Software

Learn More about this Drone-Based Vole Management Software

Mitch Lies