Irrigation Around Honeycrisp

If we are starting a new orchard, then rootstock selection is step 1. In terms of controlling vigor, having a root that is designed to grow a smaller tree such as a Bud 9, G. 11, G.41, M9-337, or a G.935 has been considered ideal for single leader trees but with rootstock availability, growers don’t always get the roots they want. G.41 has historically been tough to get from nurseries so growers may be stuck with a G.890, G.210, G.969, and in some growing conditions that’s ok. In the first couple of years, the focus should be filling space anyway, and in higher elevation orchards with a shorter growing season, having a high-powered rootstock that will fill space quickly is ideal. Another consideration is how many leaders will the tree have. A multi-leader tree either as a bi-ax or v-trellis system may need the additional push from an 890 or 210 to fill the space in the first two or three years. After the space is filled and the tree is ready for fruit, the roots will continue to produce whatever level of vigor their genetics allow. If it’s a G.11, the finished tree will have a lower vigor than a G.890 and in essence, less vigor that will need to be mitigated once bearing fruit.

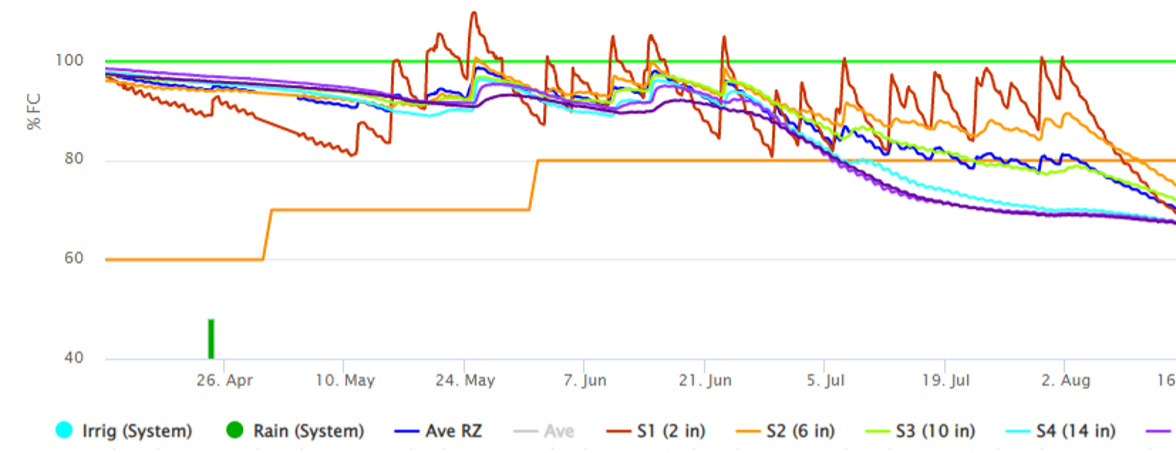

Regardless of the rootstock, elevation, variety of Honeycrisp, soil type, etc… controlling tree vigor should be the focus once there is a crop on the tree. With varieties that are not as sensitive such as Gala and Fuji’s cropping the tree before space is filled and then growing a small crop while continuing to fill space is a reasonable expectation. With Honeycrisp, growing conditions to grow the tree and a good apple are very different so filling space before a crop is ideal. Much of what I’m about to say comes with a caveat so bear with me. Honeycrisp and deficit irrigation go hand in hand so here’s the general irrigation plan with the deficit. Coming out of winter, give the trees as much water and nutrients as they need. This doesn’t mean overirrigation, this means maintaining 85%-90% field capacity in the soil to provide the roots with the correct mix of air and moisture for optimal root health and nutrient uptake. If dry fertilizer was applied, make sure it is watered in but not flushed out past the roots. (Figure 1) During this 2022 season, we have had such a wet spring in the North Cascades that many growers have only needed to apply irrigation a handful of times to keep the trees growing happy and maintain proper moisture levels.

Figure 1

The deficit begins roughly 40 days after full bloom after cell division in the apple has completed. Cell division is what you’re waiting for because we’re trying to control cell expansion within the fruitlets.

Deficit irrigation looks different for different situations. The goal here is to provide less water to the tree to stress the root system which then slows the rate of vegetative growth which in turn slows the rate of cell expansion in the fruitlet which can increase the cell integrity to decrease bitterpit. Lee Kalcsits through WSU has done multiple studies proving this methodology the results are indisputable. As a baseline, drying down the block to 70% will provide the stress needed to slow the vegetative growth. In the soil profile there is a pressure balance between the roots and available moisture. As shown using tensiometers, at 70%, there is an equilibrium between the root system and the soils hold on water molecules. Once this equilibrium is reached, the roots have to work extra hard to break the bond between water molecules and the soil particles’ surface in order to draw that water into their own structure for uptake. That being said, Kalcsits has done studies where he drew the moisture in the soil down to 40%, and where that is possible in some soils, there are also environmental forces at work to allow the soil to get that dry. Now, here’s the caveat. Once trees are under stress, the grower needs to keep an eye on several things.

The probes we’re using to monitor moisture percentages are in a single location. Some blocks may have two or three but even three probes in a 10-acre block mean the probes are monitoring .75 ft/sq out of 435,600 ft/sq. so representative placement of the probes and trust in their readings are highly important. The grower needs to have the ability to monitor the entire block and ensure they do not have exceptionally dry areas or wet areas. The more consistent the block is, the simpler this becomes.

Throughout summer and on to harvest, the grower should be tracking fruit sizing. If the fruit is still growing too rapidly, they may have to dry out the block further or if the fruit is not sizing enough then add water in small amounts. If this hasn’t been actively monitored throughout the season, small fruit at harvest can be the result and we want to add moisture when it’s needed to maintain the desired percentages. Once we get through harvest, it’s time to pump those trees back up with water and nutrients and make sure they have buds developing for the next season so we can do it all again.

Honeycrisp are nothing short of a pain to grow. Everything I’ve laid out here is strictly a baseline to start at and depending on rootstock, soil type, location, irrigation system capabilities, and grower capabilities, adjustments need to be made throughout the year. There is no silver bullet in this, but through monitoring and strict adherence to vigor control, the process of proper Honeycrisp irrigation can be learned to fit individual blocks and repeated year after year.

Curtis Pusey, Irrigation Water Management Specialist